Gut-brain connection

Intro

The gut-brain connection, aka the gut-brain axis is an intricate, bidirectional “superhighway” between the gut and the brain. The axis consists of a complex network of physiological pathways that connect the gut and brain via the vagus nerve. Insights into this gut-brain axis have revealed a dynamic communication system that not only influences intestinal activities like digestion and motility, but also regulates immune and pain response, metabolism, mood, social behavior, and cognition.

The old saying “you are what you eat” is true; however, “you are what you absorb” is just as important. Nourishing your gut lining, supporting your microbiome, and having the right digestive enzymes is vital to maintaining health.

The gut-brain connection has a bi-directional relationship which means your gut affects your brain just as much as your brain affects your gut.

This means the gut microbiota can impact essential mental and biological functions such as pain and mood¹, social behavior², and cognition³. The brain can also send signals to the gut that influence appetite, digestion, motility, and even the foods we crave.⁴

In addition, the gut-brain axis has also been linked to growing number of psychological and neurological diseases including Autism Spectrum Disorder, depression, anxiety⁵, Parkinson’s disease⁶, Alzheimer’s disease⁷, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

These breakthroughs in research not only evolves our understanding of neurology, gastroenterology, and associated pathologies, but also unlocks a novel interrelated framework to reimagine holistic naturopathic treatments.

How Does the gut and brain communicate?

The gut and brain use various forms of communication to converse. The most prominent physical connection and pathway is via the vagus nerve, one of the longest nerves in the body. Other messages are sent in the form of microbial metabolites such as organic acids (short-chain fatty acids), proteins, fats, and neurotransmitters, which reach the brain by hitching a ride through blood vessels or stimulating the vagus nerve.

One particularly compelling area of gut-brain research explores how specific microbial metabolites influence neuropsychiatric health, and how probiotic treatments may be used to control these metabolites for mental health outcomes. Researchers have discovered certain intestinal microbes and microbial metabolites contribute to neuropsychiatric conditions, as well as the molecular signals from gut bacteria that can influence anxiety behavior.

More recently, a study in Nature demonstrated that specific microbes alone could activate neuronal activity in the hypothalamus to reduce levels of corticosterone, a stress hormone in mice, known in humans as cortisol. After first confirming the link between increased levels of corticosterone and reduced microbiome diversity in mice, the research team identified a bacterial species (Enterococcus faecalis), which promotes social activity and reduces corticosterone levels following social stress.

Factors that degrade the gut-brain axis

Both chronic and acute stressors can shift both composition of the gut microbiome and contribute to intestinal permeability and the development of gastrointestinal disorders.

I. STRESS

The heightened inflammation that frequently accompanies high levels of stress triggers blooms of pathogenic bacteria that promote dysbiosis and a leaky gut.

II. POOR DIET AND NUTRITION

Poor diet and nutrition can also negatively impact the gut microbiome, and in turn, the gut-brain connection.

III. FOOD SENSITIVITIES AND INTOLERANCES

Food sensitivities, allergies, and/or intolerances triggers an immune system response that will slowly degrade your intestinal lining, cause dysbiosis, and lead to leaky gut.

IV. TOXINS

Pesticides such as glyphosate (Round-Up), fertilizers, heavy metals, mold mycotoxins, and other environmental toxins can negatively influence your microbiota and contribute to leaky gut.

V. INFECTIONS

Acute and chronic infections such as parasites, Giardia, C. difficile, H. pylori, E. coli, Covid-19, Lyme Disease, Mycoplasma, Babesia, Bartonella, and Epstein-Barr Virus can all degrade the gut-brain axis and lead to GI dysfunction.

VI. INFLAMMATION

Inflammation is an abnormal immune response, so determining the underlying imbalance(s) such as toxin load, infections, food sensitivities, stress, etc. is important when trying to revere high levels of inflammation.

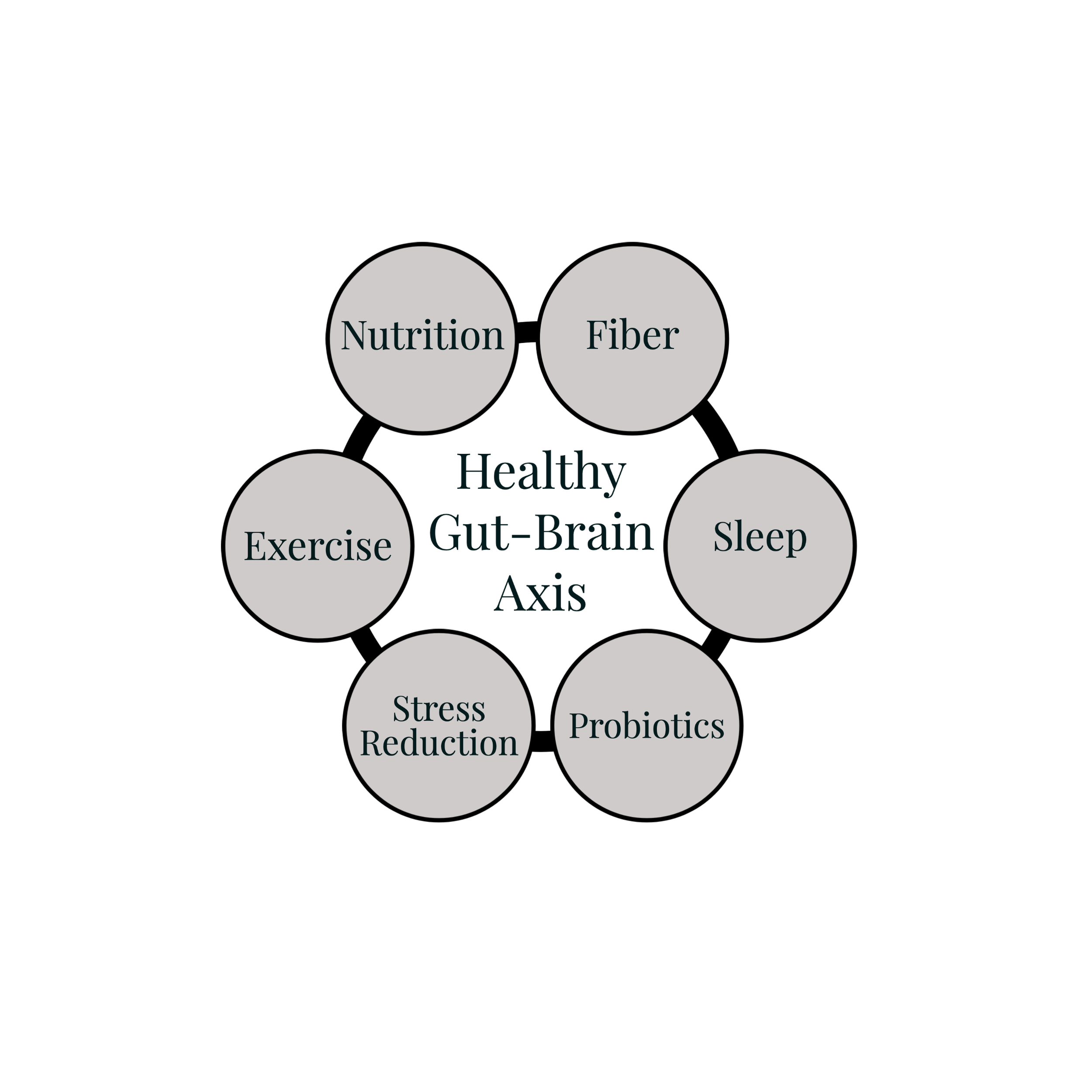

How to Support a Healthy Gut-Brain Connection

I. DIET AND NUTRITION

By far the best way we can support the gut microbiome, and in turn, the gut-brain pathway. Just as there is no one universally healthy microbiome, there is no one-size-fits-all, “perfect” diet either. Generally, however, a plant-rich diet, high in fiber, healthy fats and protein; while also being low in sugar, preservative agents, processed foods, food additives and fried foods, tends to correlate with a “healthy” microbiome.

Our gut microbes ferment dietary fiber such as berries, root veggies, and beans into compounds (like butyrate) that can impact brain and nervous system function. Butyrate is a short chain fatty acid that can positively influence vagus nerve activity.¹⁰

Did you know that 95% of serotonin (a mood regulating hormone) is produced in your gut? Well it is and the gut microbiome will increase serotonin⁹ production as a direct result of the food you we eat. Foods rich in carbohydrates and essential amino acids tryptophan (like poultry, eggs, nuts, seed, spinach).

II. STRESS REDUCTION

If nutrition is the most important factor in supporting a healthy gut-brain axis, stress reduction is a very close second. Not only can stress cause a person to overeat, eat too fast and resort to fast-food, but the continuous release of cortisol promotes sympathetic dominance (fight, flight, freeze) instead of parasympathetic (rest, digest, repair). I hope it is obvious your gut won’t be performing well if it believes you should be “running from the bear.” Stressful situations are associated with onset of symptoms and worsening of symptoms including IBD, IBS, GERD, and peptic ulcer disease.

While stress in small doses can be a good thing (think motivation to succeed, focus), it’s important to relax and not multi-task while eating. It’s also important identify your common stress triggers, learn how it manifests in your body, and find your own way to deal with the stress in your life. Meditation, exercise, and functional breathing are all coping mechanisms that can help you recover from stressful events more quickly. See the next section below for tips to reduce anxiety of worry and de-stress.

III. SLEEP

Sleep is also important for your microbiome, as microbes follow their own circadian rhythms and require rest to stay in balance. Evidence shows that sleep patterns can affect the microbiome and the gut-brain connection, so it’s valuable to prioritize rest.

IV. EXERCISE

Additionally, regular exercise is significant for the gut-brain connection. Movement is helpful in stress management, and research has shown that moderate physical exercise positively modulates the relationship between the gut and brain.

V. PROBIOTICS

- Typically start with a blend of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains, but the probiotics are further refined based on your symptoms and stool testing results. For example, there are certain bacteria that promote production in histamine and thus must be avoided if you struggle with mast cell disorders.

Supporting gut-brain with stress reduction

FUNCTIONAL DIAPHRAGM BREATHING

Stress can cause shallow breathing, which means that your body won’t get enough oxygen to fully relax. Learn to breathe more slowly and deeply from your abdomen. One way to do this is to imagine that you have a small beach ball behind your belly button, which you slowly inflate and deflate.

SPEND TIME OUTDOORS IN NATURE

- Take time away from your cell phone and computer to connect with nature. The colors, sounds, and fresh air is grounding for your nervous system. It will help discharge anxiety and give you a sense of peace.

EXERCISE

Exercise is a well-known tension reducer and can help relieve symptoms. The paradox is that strenuous, high-impact exercises might induce GERD symptoms, so take care to increase exercise slowly and assess your body’s tolerance to this as you do.

LEARN TO SAY NO

Thinking you can ‘do it all’ creates unnecessary pressure. Learn how to set boundaries for yourself. Politely – yet firmly – turn down additional responsibilities or projects that you don’t have the extra time or energy for. Don’t feel obliged to give long, detailed explanations as to why. A simple, “I’d love to help you out, but I’m booked up,” will usually do in most cases.

TAKE PERSONAL TIME

Our minds and bodies require a certain amount of variety, or else our overcharged nervous systems will keep speeding right into the next day. Try to take at least one day off each week to do something you really enjoy, whatever that may be. Remember to include things like getting enough sleep, exercising your faith, having a leisurely bath, listening to music, playing with a pet, having conversations with friends, or anything that gives you pleasure.

LAUGH IT OUT

Laughter is a natural stress reliever that helps to lower blood pressure, slow your heart and breathing rate, and relax your muscles. How do you tickle your funny bone? Catch comedies, have a chuckle with a friend, and make an effort to look on the lighter side of life.

CHOOSE FOODS CAREFULLY

Some foods can increase your stress level while others can help reduce it. Generally, fatty, sugary, and/or processed foods seem to increase stress in most people while lean meat, whole grains, and fresh fruits and vegetables seem to decrease stress. Choose foods wisely and in addition to reducing stress, your body will love you for it!

Hiking in a forest is an excellent way to de-stress.

Citations

Rhee, S. H., Pothoulakis, C., & Mayer, E. A. (2009). Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 6(5), 306-314.

We, W. L., Adame, M. D., Liou, C. W., Barlow, J. T., Lai, T. T., Sharon G., Schretter, C. E., Needham, B. D., Wang, M. I., Tang, W., Ousey, J., Lin, Y. Y., Yao, T. H., Ahdel-Haq, R., Beadle, K., Gradinaru, V., Ismagilov, R. F., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2021). Microbiota regulate social behaviour via stress response neurons in the brain. Nature, 595(7867), 409-414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03669-y

Jenkins, T. A., Nguyen, J. C. Polglaze, K. E., & Bertrand, P. P. (2016). Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis. Nutrients, 8(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010056

Madison, A., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2019). Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human-bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Current opinion in behavioral sciences, 28, 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.01.011

Foster, J. A., & McVey Neufeld, K. A. (2013). Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends in neurosciences, 36(5), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005

Keshavarzian, A., Green, S. J., Engen, P. A., Voigt, R. M., Naqib, A., Forsyth, C. B., Mutlu, E., & Shannon, K. M. (2015). Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 30(10), 1351–1360. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26307

Kowalski, K., & Mulak, A. (2019). Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility, 25(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm18087

Wu, W. L., Adame, M. D., Liou, C. W., Barlow, J. T., Lai, T. T., Sharon, G., Schretter, C. E., Needham, B. D., Wang, M. I., Tang, W., Ousey, J., Lin, Y. Y., Yao, T. H., Abdel-Haq, R., Beadle, K., Gradinaru, V., Ismagilov, R. F., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2021). Microbiota regulate social behaviour via stress response neurons in the brain. Nature, 595(7867), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03669-y

Bruta, K., Vanshika, Bhasin, K., & Bhawana. (2021). The role of serotonin and diet in the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a systemic review. Translational medicine communications, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-020-00081-y

Berding, K., Carbia, C., & Cryan, J. F. (2021). Going with the grain: Fiber, cognition, and the microbiota-gut-brain-axis. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 246(7), 796-811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370221995785